We use cookies to make your experience better.

To comply with the new e-Privacy directive, you agree to the privacy policy and our use of cookies.

A little tour of Trewell Common and East Anglian heritage

Common land and the heritage of the societies that lived around them in East Anglia

Before the enclosures in England, a portion of the land was categorized as "common" or "waste". "Common" land was under the control of the lord of the manor, but certain rights on the land such as pasture, pannage, or estovers were held variously by certain nearby properties, or in gross by all manorial tenants. "Waste" was land without value as a farm strip – often very narrow areas in awkward locations (such as cliff edges, or inconveniently shaped manorial borders), but also bare rock, and so forth. "Waste" was not officially used by anyone, and so was often farmed by landless peasants.

The remaining land was organised into a large number of narrow strips, each tenant possessing a number of disparate strips throughout the manor, as would the manorial lord. Called the open-field system, it was administered by manorial courts, which exercised some collective control. What might now be termed a single field would have been divided under this system among the lord and his tenants; poorer peasants were allowed to live on the strips owned by the lord in return for cultivating his land.

The terms "commoner" and "common people" come from the terms used to describe the people that worked and lived on these common lands.

Seeking better financial returns, landowners looked for more efficient farming techniques. Enclosure acts for small areas had been passed sporadically since the 12th century but advances in agricultural knowledge and technology in the 18th century made them more commonplace. Because tenants, or even copyholders, had legally enforceable rights on the land, substantial compensation was provided to extinguish them; thus many tenants were active supporters of enclosure, though it enabled landlords to force reluctant tenants to comply with the process.

With legal control of the land, landlords introduced innovations in methods of crop production, increasing profits and supporting the Agricultural Revolution; higher productivity also enabled landowners to justify higher rents for the people working the land. In 1801, the Inclosure (Consolidation) Act was passed to tidy up previous acts. In 1845, another General Inclosure Act instituted the appointment of Inclosure Commissioners, who could enclose land without submitting a request to Parliament.

The tenants displaced by the process often left the countryside to work in the towns. This contributed to the Industrial Revolution – at the very moment new technological advances required large numbers of workers, a concentration of large numbers of people in need of work had emerged; the former country tenants and their descendants became workers in industrial factories within cities.

A poem from the 18th century reads as a protest of the inclosure acts:

They hang the man and flog the woman

Who steals the goose from off the common

Yet let the greater villain loose

That steals the common from the goose

The law demands that we atone

When we take things we do not own

But leaves the lords and ladies fine

Who take things that are yours and mine

The poor and wretched don't escape

If they conspire the law to break

This must be so but they endure

Those who conspire to make the law

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common

And geese will still a common lack

Till they go and steal it back

Traditional housing

Life was hard in pre-industrial England; farmland was less workable, and people eked a living off what land they could. The houses of the poor were often manorial buildings for the servants of the manor or were built wherever possible and all were made from local materials

Oak, which was common in the British countryside, was the predominant framing material for these dwellings. A stone base was laid down as a foundation then the timbers worked by teams of people and all the timbers jointed locking the structure together. The endurance of this building system is plain to see as even 500 years on you can still see examples of these houses, twisted, warped, but still standing. The strength of the frame came from the jointing mechanisms used and the kills of the carpenters to manipulate the material.

The panels in the frame were filled in with wattle and daub, a system of weaving sticks (mostly willow) and then ‘Daubed’ with a mixture of earthy material and straw. The panel was then finally rendered with lime to protect it if the money was to fund that process. Later these panels were often replaced with a brick or stone infill, this added better insulation and rigidity to the structure.

The manufacturing processes, cost of glass (and eventually the window tax) caused windows and apertures in the walls to be small and infrequent, the limitations on glass remained hight until the industrial invention of float glass in the 1950’s

Roofs were mostly thatched due to the costs associated with earthen ceramic tiles until industrialisation facilitated the switch from reed a straw to ceramic tiles in the 1800’s

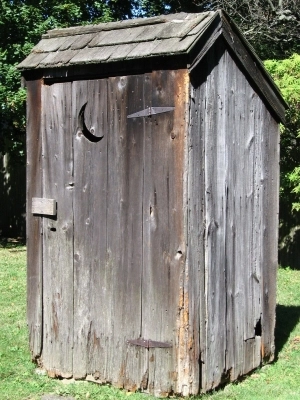

As part of the set, we also have an outhouse in the social stretch goals to complete the homestead. Before the days of internal plumbing and flushing toilets, the toilet was situated in small rooms built out in the garden, often with a bucket under the seat or a pit dug underneath them. These outhouses were small and rather unpleasant on winters nights.

Post and rail fences

Post and rail fences are a simple wooden construction that is found all across East Anglia. It is cheap to erect and during times gone by the material was grown locally and easy to source. Used to boarder land boundaries or a cheap alternative for garden fencing.

Windmill’s

Thelnetham’s windmill is situated a few miles from the site of Trewell Common and on Joseph Hodgekinson’s map of Suffolk from 1778 shows a mill situated on a site close to its current location also situated on a strip of common land. Local records show that this was a post mill owned by William Button and that he decided to replace it with a tower mill, early in the 19th century. The original post mill was recorded as being sold and transported to another location nearby in a field near Diss.

The mill ceased operation in 1920 after the introduction of the governments flour restrictions in 1916. The mill was then sold to a retired millwright from Blo-Norton (the site of Trewell Common). After the death of the millwright the mill began its decline until it was purchased by a group of enthusiasts in 1979. This group preserved and restored the mill, and it is now one of only four preserved tower mills in Suffolk and one of the few full working mills in East Anglia.

The mill trust has a website which can be viewed here: https://thelnethamwindmill.org.uk/

The Upthorpe post mill located in Stanton (not far from the site of Trewell Common) was built in 1751 as an open trestle post mill. It was moved to its present location in 1818 and its sails were updated in line with more modern standards. The lower roundhouse and fantail mechanism were fitted at a later date. The mill was used until 1918 and then fell into disrepair.

Flint Churches of East Anglia

Forming a huge part of the landscape, heritage, and culture of the East Anglian countryside, erected to serve the local parishes all over the land and to watch over the people. They have taken many forms and sizes; they have been rebuilt and altered across the centuries however they endure as a testament to the communities they were the centre of.

As with all structures of the time they were made from local materials, which in East Anglia is predominantly flint. This material forms a rough textured skin and can be dressed to form a flat black glassy finish. These would have wooden framed roofs and would often have been thatched but later converted to tiles when there was availability.

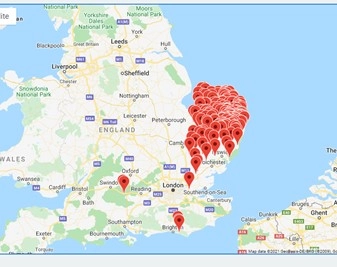

The churches range from small structures to towering edifices and can be seen from mile away. The characteristic towers stem from the Norman invasion. Erected as part of the socio-political conquest of the Anglo-Saxons these buildings spread the message that the Normans were here to stay and they were indeed favoured by god. Over the reign of 4 kings over 7,000 churches were built across the land, of these about a quarter remain to the present day and around 2,000 original Norman churches can still be visited today.

The towers are usually attached to the main church, square in shape and stepped up to the top. There are however exceptions to this for example in Little Snoring, Dereham, West Walton, Beccles and Bramfield (all within East Anglia) the tower is separated from the main church building. Also, in East Anglia there is a high concentration of churches with round towers. The strange concentration of round church towers can be seen on this map.

Gravestones

The ornamentations are ubiquitous in churchyards the world over and are laid in tribute and memorial of the occupant of the grave. Often with a short epitaph and denoting key events or characteristics of their life and displaying the birth and death date of the person in question.

Originally made from local materials the stones or even simple wooden crosses, if the family of the person in question was particularly wealthy then the stone could be made of more exotic materials or become a grander monument entirely.

And Now a Musical Interlude

Beacons

Across the UK there are many places named beacon hill and even an entire region called the Brecon Beacons, these places were named after the chain of elevated baskets filled with combustible material that were used as a form of warning communication chain across the country. Mostly found in the highest point of an area and spaced across the landscape so that one can be seen from the last when lit.

These have been used at many times in English history, famously to warn of the approach of the Spanish armada or in Wales to warn of approaching English raiders.

In England, the authority to erect beacons originally lay with the King but was later delegated to the Lord High Admiral.

The beacons required maintenance and the money for that was levied by the sheriff of each county and was called a beaconagium.

Today the beacons are still lit to celebrate or mourn. Most recently they have been lit in memorial of 100 years since the end of World War 1. Prior to that they were lit to celebrate the silver jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II.

Flint Walls

Ubiquitous to the East Anglian region flint walls form the boundaries of pastures and property everywhere in the region. They consist of two faces that were laid down behind shuttering, bonded with lime mortar and then back filled with rubble and mortar mix. The runs are laid between brick or stone piers and as usual consist of locally found materials.

In the region of Trewell Common you can find all sorts of odd-shaped stone within the walls as well these come from destroyed buildings and local legend says that mostly they originate from the destroyed abbey in Bury St Edmunds. During the dissolution of the monasteries the abbey was pulled down by the townspeople and then the materials were stolen and used in many local constructions.

Ickworth house Rotunda

Ickworth house is a manor house situated near Bury St Edmunds. The manors history dates back to before the Doomsday book (the 1086 Great Survey by William the conqueror for tax collection purposes) where it was owned by the abbey. It became the home of the Hervey family in 1432 and remained so for 500 years.

The manor underwent many changes from medieval hall to turreted mansion before being demolished again and rebuilt in an even grander form. The plans for, and construction of the rotunda was carried out during the 1700’s.

The building remains unique in Great Britain, its design takes influence from Italian architecture and concieved by Irish architects ‘The Sandy Brothers’.

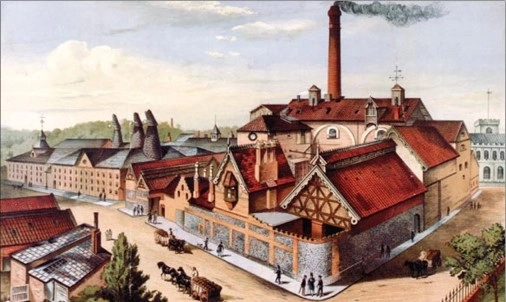

Brewery

The hub of every local community is the pub, and every pub needs a supplier, the local economy of Trewell Common would not be complete without a brewery.

East Anglia itself always has been full of breweries of all scales. Beer has been a staple of the English culture since the dark ages. Bury St Edmunds is home to the Green King brewery and on the coast is the Adnams brewery as the most notable ones in the area, however currently there are still around 300 micro-breweries in East Anglia making beer production high on the list of industry.

Humpback Bridge

This bridge was inspired by the humpback bridge at Knetteshall heath that is only a stone’s throw from the site of Trewell Common.

Bridges, fords, and crossings have long made sites for settlements. They serve as key points in trade routes and often were constructed and maintained by landowners then operated by tolls.

Constructed, again using local materials often wood or stone, this bridge uses the traditional flint construction used most East Anglian construction with brick detailing.

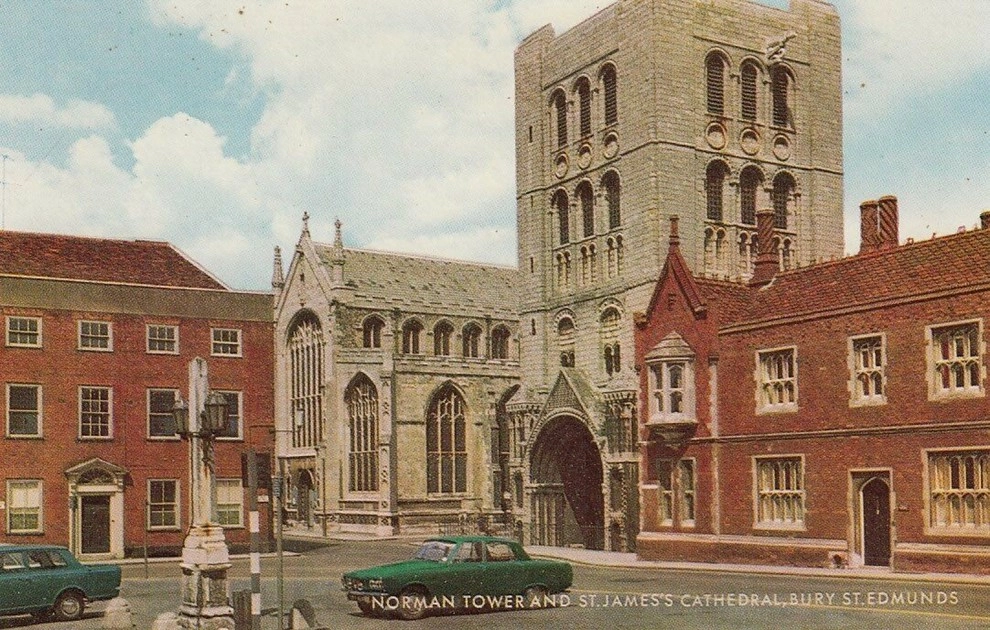

The Norman Tower

The Abbey in Bury St Edmunds was one of the central landmarks in the region that Trewell Common represents for hundreds of years. It was a site of religious use since at least the 7th century, in the 10th century the relics of the martyr St Edmunds were transferred to the site.

The Norman Tower was a monastic gate, now used as a belfry for the Cathedral Church of St James. The tower was built under Abbot Anselm between 1120 and 1148 in a Romanesque style. The tower was restored by LN Cottingham in 1846/7. The tower was made from Barnack stone.

Rectangular in shape, in 4 stages, with the base now well below the present ground level. It is richly ornamented with a large, unvaulted gateway has heavy block capitals to the columns and large roll-mouldings. The west face is the most ornate, with a sculptured inner order and the arch projecting like a porch with a gable and fish scale decoration. To each side of the gateway are 2 tiers of niches with billet decoration; short buttresses above have intersecting arches and pyramid roofs. The 2nd stage has 2 tall blank arches with small 2-light windows within them. The 3rd and 4th stages each have 3 deep window openings, divided by colonnettes and hood-moulds with billet decoration: below the 3rd stage openings are paired blank arches; below the 4th stage blank roundels. The details of the 3 upper stages on the west are repeated on each of the other faces.

The abbey church that was subsequently built was one of the largest in the country with a transept of 505ft long and 246ft wide.

The abbey was torn down in The Great Riot by the towns people in 1327, They were angry at the power of the monastery and it had to be rebuilt.

In the 11th century the abbey was granted the control of the surrounding lands. The abbey’s charters granted extensive land rights in Suffolk and by 1327 the abbey owned all of West Suffolk. The rights of the abbey extended to holding the gates of Bury St Edmunds, wardships over all orphans (who’s income went to the Abbot until the orphan reached maturity), the abbey held rights of corvee (a form of temporary servitude) over the towns people and forced their rights on the populace (an example is the forced destruction of a new windmill built without permission in the 12th century).

The town of Bury St Edmunds was designed by the monks in a grid pattern. Tariffs were charged on all economic activity, even down to the collecting of horse droppings in the street. The Abbey was even in charge of running the Royal Mint. During the 13th century the prosperity of the area kept the populace at bay, but in the early 14th century a series of riots resulted in the death of several Abbots and the destruction of many buildings. In January of 1327 the towns people attacked which forced a charter of liberties to be created, this was then ignored by the monks which forced more action by the townspeople in February and May. During those attacks, the charters and debtors accounts were seized and destroyed.

In September 1327 the Abbey was visited by Queen Isabella (with her son the future king Edward III) and her army to aid in the subduing of the townspeople. After her departure, the conflict escalated in October when a group of monks entered a local parish church wearing armour beneath their habits. They took several hostages, despite the pleas of the townspeople for their release the monks refused and responded by throwing objects at the crowd, killing some of them. This caused the citizens to swear they would fight the Abbey to the death, this included a parson and 28 chaplains. They eventually burned the gates and captured the Abbey.

After this period of unrest, the Abbey faced considerable financial strain and began falling into decline, in 1431 the west tower of the abbey church collapsed. King Henry VI took great advantage of the monastic hospitality of the Abbey in 1433. The death of the Duke of Gloucester in 1447 in suspicious circumstances after his arrest caused more trouble for the Abbey and then in 1465 the entire church was burned out by an accidental fire.

The Abbey was largely rebuilt by 1506 and had a relatively quiet existence until the dissolution of the monasteries in 1539 which saw the Abbey stripped of all valuable materials and artefacts, the ruins were then left as a quarry for local builders.

A relic from the abbey can also be seen in the metropolitan museum of art in Ney York City, The Cloisters Cross, also referred to as the "Bury St Edmunds Cross", is an unusually complex 12th-century Romanesque altar cross, carved from walrus ivory.

The Gibbet Cage

Gibbeting was a common law punishment used extensively for crimes of all types in English history. Although a gibbet is a term used for any method of public execution, in England it is more commonly associated with a body shaped cage where a man could be hung from gallows until dead and then left as a warning for an extended period.

This form of punishment was most used in response to traitors, murderers, highwaymen, sheep stealers and pirates.

Moyses hall in Bury St Edmunds has a Gibbet cage that was found complete with John Nichols’ skeleton still inside during the building of Honington Aerodrome in the late 1930s.

Nichols and his son Nathan were tried and hanged for murder at Bury St Edmunds in March 1794. Nathan Nichols’ body was dissected and anatomised. His father’s remains were gibbeted near the site of the murder. The victim was Nichols’ own daughter, Sarah. She had been bludgeoned with a hedge-stake and strangled. Her body was discovered a few hours later lying in a ditch. The Edinburgh Advertiser published a short and gruesome account at the time. (pictured)

The motive for the murder is not recorded. Neither father nor son showed any remorse, and each went to the gallows accusing the other of the crime.

Herringbone manor house

The map of England has long been divided by the upper class into small patches of land. These seats of power were owned and operated by lords, these lords were the main employers in the region and supported hundreds of families on their estate. These families were workers and servants on the land and in the manor houses, often through the generations.

Manor houses were often grand affairs built in a style befitting the lord of the time. These houses were often added to and changed across the generations and due to the status and wealth of the lord used materials sourced from all over and not the local materials used for the workers cottages.

A popular style for these houses was to use brick. To add a flair, it often took on a herringbone style. This is a style of brick laying where the bricks were at 45 degrees to the horizontal and interlaced to create decorative pattern.

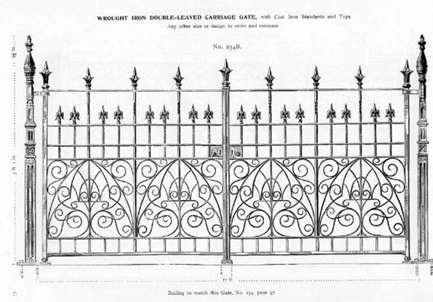

Wrought Iron Fence Panels

Wrought iron work has long been coveted for its simple beauty, hand crafted by blacksmiths in local forges the shapes and patterns require skill, time, and patience to produce. This type of work has been a luxury item afforded to the richest households or churches.

Weathervane

A weathervane, wind vane or weathercock is a traditional instrument to show the direction of the wind. Typically seen as an architectural ornament mounted to the highest point of a building. The word ‘vane’ comes from the old English word ‘fana’, meaning ‘flag’.

The weathervane was independently invented in ancient China and Greece around the second century BC

Sundials

A sundial is a simple device to allow you to tell the time of day by the position of the sun relative to the earth and date back to the earliest known civilisations.

Gypsy Caravan

Although Gypsy and Traveller communities are often viewed as outside and distinctly separate from ‘ordinary’ settled society, the truth is that across both economic and social spheres the two peoples were deeply connected. For many rural communities in Britain – particularly for farmers – monetary success stemmed from a high degree of engagement with Gypsies and Travellers during their annual journeys across Britain for casual and seasonal work, fairs, and family events. May marked the beginning of the travelling season, as this was the time when most families would head out in their wagons to do agricultural work. Whilst the type of work varied, the harvesting of various seasonal crops acted as important annual markers; June was the time for pea picking, whilst Hop picking season in September.

This concludes our little tour of East Anglian rural history, we hope you have enjoyed learning about our heritage and further we hope you will enjoy the models that come from Trewell Common.

We hope to do far more like this in the future for other areas of local history and culture. Let us know what you think in the Digital Taxidermists Facebook Group.

If you like this and would like to help us produce more articles like this then feel free to drop a donation to our research team using the button below.

-

Trewell Common - Fantasy Historical English Village - Kickstarter Pack

Special Price £49.99 Regular Price £59.99